Measure Success with DORA Metrics - Part 2 - Plan

Planning is where teams win or lose. Not in execution, but in deciding what to execute, how to scope it, and who gets a voice.

Most teams treat planning as an administrative hurdle. A meeting to get through so they can start the real work. That's backwards. The planning phase sets the trajectory for everything that follows. Scope work too large and you'll spend months delivering something nobody wants. Exclude infrastructure engineers from prioritization and you'll accumulate technical debt that eventually stops feature development cold. Let bad news stay buried and you'll be blindsided by problems that were visible to someone on the team weeks ago.

In Part 1, I introduced the software development lifecycle I use: Plan, Build, Deploy, Release, Operate, Monitor. Each stage has capabilities that predict performance, and performance predicts business outcomes. That's the DORA model. In this post, we're going deep on Plan, the stage where culture, process, and leadership converge to determine whether the rest of the cycle even has a chance.

Culture Is the Operating System

Before we talk about backlogs and prioritization meetings, we need to talk about culture. Not the "we have ping pong tables" kind. The kind that determines whether information flows or gets stuck.

Ron Westrum, a sociologist who studied high-risk industries like aviation and healthcare, identified three types of organizational culture based on how they process information:

Pathological cultures are power-oriented. Cooperation is low. Messengers get punished. When something goes wrong, someone gets blamed. New ideas get crushed because they threaten the existing power structure.

Bureaucratic cultures are rule-oriented. Cooperation is modest. Messengers get neglected, not punished, just ignored. Responsibilities are narrow and siloed. New ideas create problems because they don't fit existing processes.

Generative cultures are performance-oriented. Cooperation is high. Messengers are trained, and the organization actively wants bad news so it can fix problems early. Responsibilities are shared. Failure leads to inquiry, not blame. New ideas get implemented.

DORA's research validated what Westrum found: generative cultures predict both software delivery performance and organizational performance. Google's two-year study on team effectiveness found the same thing. High-performing teams need psychological safety, meaningful work, and clarity. This is the capability DORA calls Generative Organizational Culture, and it's foundational to everything else.

The planning phase is where culture shows up first. Consider what happens when someone brings bad news to a planning meeting. The infrastructure engineer who says "we need to upgrade the database before we can build this feature" or the developer who says "the estimate for this is way off, we're looking at three months, not three weeks."

In a pathological culture, that person learns to keep their mouth shut next time. In a bureaucratic culture, the information gets logged somewhere and ignored. In a generative culture, the team adapts because the goal is performance, not protecting anyone's ego or preserving the original plan.

If you're a founder or CTO, your behavior in planning meetings sets the tone. Do you reward people who surface problems early? Do you change direction when new information contradicts the plan? Or do you shoot the messenger and wonder why nobody tells you anything until it's too late?

Everyone mentally agrees they want a generative culture. But if you receive bad news and don't make any plans, or delay addressing it in favor of a shiny feature, you're not there. Messengers want to feel heard. They want to know you understand the impact of what they're telling you. If it wasn't important to them, they wouldn't bring it up. When you hear bad news, make it a point to investigate. Not everything needs to be acted upon, but it needs to be validated and the risks assessed.

In Team Topologies, Matthew Skelton and Manuel Pais emphasize cross-functional teams with shared responsibility. That structure only works if the culture supports it. You can reorganize your teams into stream-aligned and platform topologies all you want. If people don't feel safe sharing information across boundaries, those boundaries will calcify into silos.

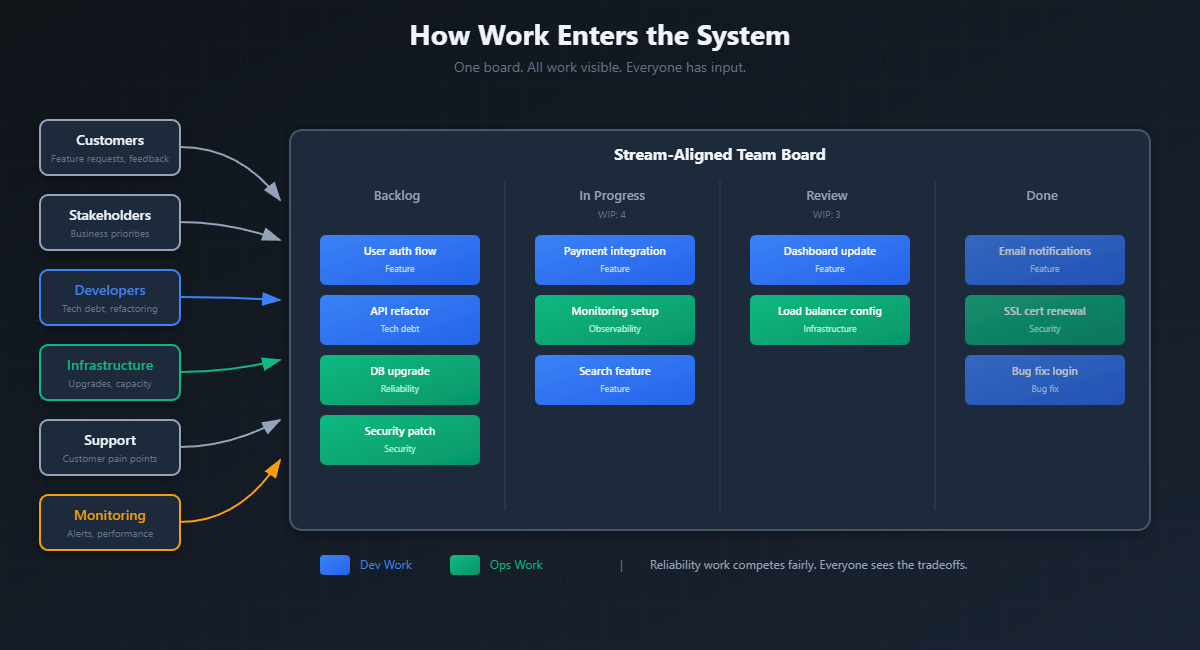

How Work Enters the System

Every team has more ideas than capacity. The planning phase is where you decide which ideas become work, and which work gets done first.

The typical flow looks like this: ideas come from somewhere (customers, stakeholders, the team itself), they get captured in a backlog, and then they get prioritized into whatever execution cadence you use, whether that's sprints, cycles, or continuous flow. Simple enough. But most teams get this wrong in predictable ways.

Who Has Input

The first question is who gets to add ideas to the backlog and who gets a voice in prioritization.

In many organizations, this is limited to product managers and executives. That's a mistake. Developers see technical debt that's slowing them down. Infrastructure engineers see stability risks that aren't visible to anyone else. Support teams hear customer pain points that never make it into formal feedback channels.

Everyone who touches the software development lifecycle should have input into what gets worked on. That doesn't mean every idea gets prioritized. It means every perspective gets heard before prioritization happens.

This is what DORA calls Visibility of Work in the Value Stream. Teams need to understand how work flows from idea to customer, and they need visibility into that flow. If infrastructure engineers don't have visibility into the feature roadmap, they can't anticipate capacity needs. If developers don't have visibility into customer feedback, they're building blind.

Reliability Work as Equal Citizen

Here's where most growth-stage companies go wrong: they treat infrastructure and reliability work as second-class to feature development. OS updates, security patches, database upgrades, capacity planning. These compete with features for prioritization, and features usually win.

Until they don't. Until you have an outage because you deferred that database upgrade for six months. Until a security vulnerability makes the news because the patch sat in the backlog behind "more important" work.

Reliability work isn't at odds with feature work. They're both necessary for delivering value to customers. The key is recognizing that infrastructure work belongs on the same board as feature work.

If you have infrastructure engineers or SREs supporting a stream-aligned team, their tasks should be visible on that team's backlog. The database upgrade, the capacity planning, the security patch. These sit alongside feature work and get prioritized together. The whole team sees what's being worked on and understands the tradeoffs.

The SRE or platform team's board then becomes an aggregation of all infrastructure work assigned across stream-aligned teams. It's not a separate backlog competing for attention. It's a view into the infrastructure commitments already prioritized within each stream.

In Team Topologies terms, platform teams aren't just servicing requests from stream-aligned teams. They're maintaining and improving the platform that enables those teams to deliver. But the work itself is visible where the prioritization happens, on the stream-aligned team's board.

This connects back to generative culture. In a generative organization, quality, availability, reliability, and security are everyone's job. That shared responsibility shows up in planning. Reliability work gets prioritized alongside feature work because everyone sees it, and everyone understands that one enables the other.

Backlog Grooming as Discipline

Backlog grooming, sometimes called refinement, is where the team reviews upcoming work, clarifies requirements, and estimates effort. Most teams treat this as a meeting to suffer through. It doesn't have to be.

Good backlog grooming accomplishes several things: it surfaces ambiguity before work starts, it identifies dependencies that could block progress, and it gives everyone a shared understanding of what "done" means for each piece of work. It sets clear expectations early and offers a time for questions to be raised and work involved discussed.

The mechanics vary. Some teams have dedicated grooming meetings. Some do it continuously as part of their flow. The specific approach matters less than the discipline. Before work gets prioritized, the team understands what it actually entails. And it needs to happen early enough that progress isn't blocked waiting for stakeholder answers.

Early on, this might be a dedicated role. Someone owns the backlog and facilitates grooming sessions. As the team matures and the discipline becomes habit, the responsibility becomes more distributed. The product manager still prioritizes, but the whole team participates in refining work items because that's just how work flows.

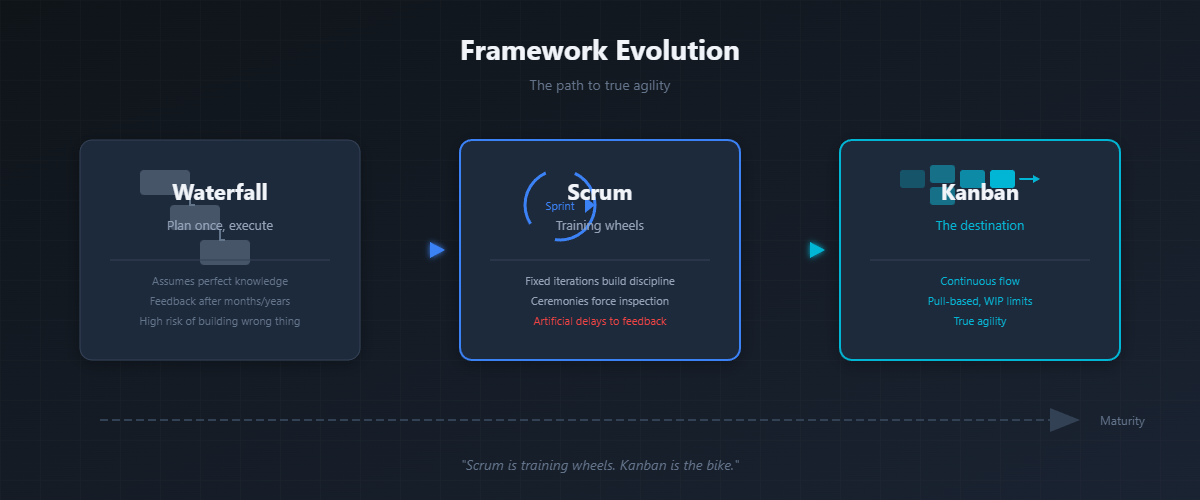

The Framework Evolution: Waterfall to Scrum to Kanban

There’s a lot of discussion on the “right” way to do agile. You'd be hard pressed to find a team that calls themselves waterfall anymore. Most have adopted agile practices in the form of Scrum. Scrum isn’t bad, but it isn’t the final stage. Kanban planning practices elevate a team operating in scrum and propel them to being truly agile.

Agile is the concept of being able to respond to market changes as fast as you can write the feature. If you’re waiting on a sprint to be finished before you ship code, you are artificially delaying market adoption and feedback.

There is not “right” or “wrong” way to do agile. Your team should be experimenting to discover what works best for them. However, everyone should be striving to have a continuous flow from planning to production.

Let me explain.

Waterfall: The Illusion of Perfect Knowledge

Waterfall planning happens once, at the beginning. You gather requirements, write a specification, estimate timelines, and execute the plan. The assumption is that you know enough upfront to plan everything in advance.

This works for some domains. Building a bridge, for example, where the requirements are well-understood and the physics don't change. It doesn't work for software, where requirements evolve as users interact with what you've built, and the competitive landscape shifts while you're executing.

Anyone who’s written software knows that you can’t know everything upfront, and the things you do know often change. Software is about always becoming, never arriving.

Waterfall's failure mode is delivering something nobody wants, months or years after it would have been useful.

Scrum: Learning to Iterate

Scrum broke the waterfall model by introducing fixed-length iterations called sprints, with planning at the start of each one. Instead of planning everything upfront, you plan enough for two weeks, execute, review what you built, and adapt.

The ceremonies matter: sprint planning, daily standups, sprint reviews, retrospectives. These rituals force teams to regularly stop, assess, and adjust. For teams coming from waterfall, this structure is essential. It builds the muscle memory of iterative delivery.

Scrum also introduces roles. The Scrum Master facilitates the process. The Product Owner prioritizes the backlog. These roles exist because teams learning to iterate need explicit support. Someone has to enforce the discipline until it becomes habit.

Be cautious though. If your sprints are long, or you’re not shipping anything for multiple sprints, you may find you’re in this hybrid scrumfall method. Here, you get all the bureaucracy of scrum, and all the rewrites and delayed value of waterfall.

Again, scrum isn’t bad. It has its place. But scrum places artificial barriers on unlocking agility. Scrum forces teams to learn to walk before they run. Once teams start bashing up against these barriers, it’s time to grow.

Kanban: Continuous Flow

Kanban takes iteration to its logical conclusion: why batch work into sprints at all? Instead of planning in cycles, you pull work from a prioritized backlog as capacity becomes available. Work flows continuously. Planning becomes ongoing rather than event-based.

The key constraint in Kanban is work-in-progress (WIP) limits. You can only have so many items in each stage of your workflow at any time. This forces you to finish work before starting new work, a discipline that sounds obvious but most teams violate constantly.

But WIP limits only work if your definition of done is right. Development teams often have the most ability to impact delivery, but not much responsibility for what happens after code is written. If done means "code complete," developers move on and the work piles up downstream. If done means "running in production with users using it," the WIP limit forces accountability through the entire flow. Your definition of done determines whether WIP limits create real discipline or just shift the bottleneck. Your team, however, needs to be structured to support your definition of done. We’ll talk more about the definition of done later.

DORA identifies both WIP Limits and Visual Management as capabilities that predict software delivery performance. A Kanban board makes work visible. WIP limits prevent overload. Together, they create flow.

Kanban requires more maturity than Scrum. Without the ceremonies forcing regular inspection, teams need internalized discipline to maintain flow. That's why Scrum often comes first. The ceremonies build the habits that make Kanban possible.

The Role That Works Itself Out of a Job

The goal of a Scrum Master is to work themselves out of a job.

Not out of the company, but out of the role as it was originally defined. A good Scrum Master doesn't run ceremonies forever. They build the discipline in the team until the team doesn't need the ceremonies anymore. They coach the team toward self-organization, and then they're free to focus on something else.

This is the same arc as DevOps engineers. A DevOps engineer isn't there to be the permanent bridge between dev and ops. They're there to break down silos, shift mindset, and embed infrastructure thinking into how developers work. Success means the team thinks about deployment, observability, and reliability from the start, not as an afterthought handed off to a specialist.

Both roles are bootstrapping functions. The Scrum Master who matures a team from Scrum to Kanban has succeeded. The DevOps engineer who gets developers including infrastructure considerations in their planning has succeeded. In mature organizations, these responsibilities don't disappear. They become distributed. The dedicated role might evolve into an advisor who helps answer questions and maintains standards across teams, but the day-to-day work is owned by the team itself.

DORA calls this Team Experimentation. Teams that can work on new ideas, change specifications, and make decisions without having to ask permission from people outside the team. That autonomy is the end state. The roles that help teams get there are means, not ends.

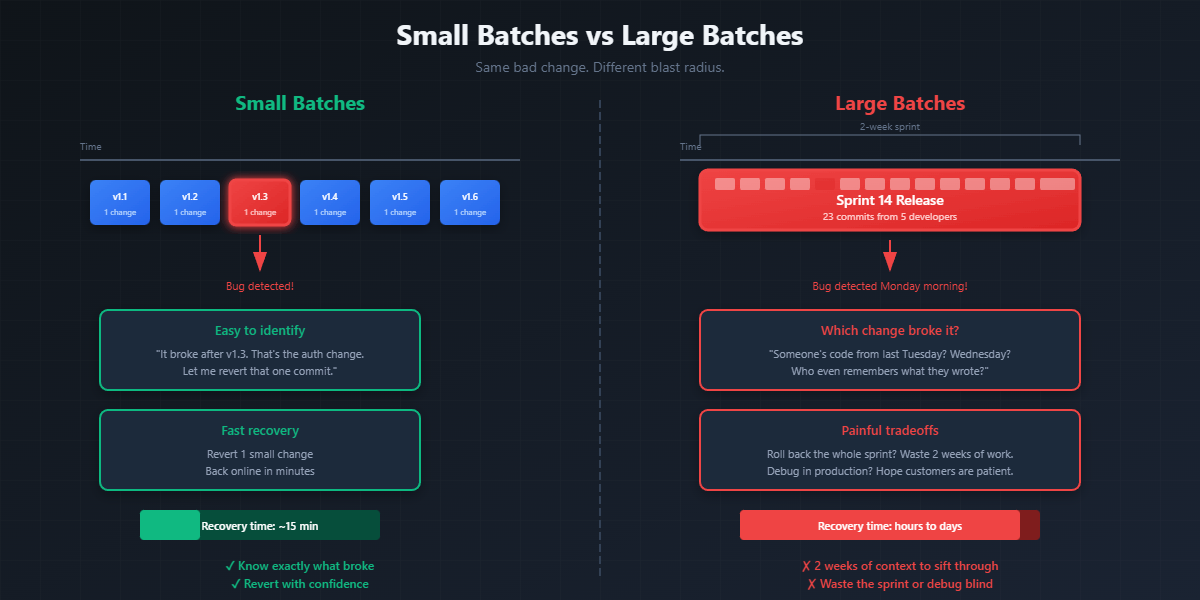

Working in Small Batches

Batch size is a planning decision. How you scope work determines how quickly it can flow through the system and deliver value.

DORA identifies Working in Small Batches as a capability that predicts both software delivery performance and organizational performance. The reasons are straightforward:

Small batches reduce feedback time. If you ship a small change and something breaks, you know what caused it. If you ship six months of changes and something breaks, good luck figuring out which change is responsible.

Small batches reduce risk. A small change that doesn't work can be reverted or fixed quickly. A large change that doesn't work might not be recoverable. You've invested too much to abandon it, even when you should.

Small batches increase throughput. Teams who experience a lot of bugs or a difficult release process will start to release less often, with more changes. The thought is that there's less risk if there's a chance for the system to go down only once a quarter instead of every other week.

Experienced leaders recognize this is a fallacy and have to be on guard to identify when a team is starting to head this direction. Releasing smaller changes more often introduces less risk and lets you recover faster. And if your release process is painful, releasing more frequently forces the team to address the pain points. The process gets smoother because it has to.

Counterintuitively, doing less at once lets you deliver more over time. You're not waiting for a massive batch to be "ready." You're continuously delivering value.

The INVEST principle provides a framework for scoping work items: Independent (can be completed without dependencies on other work), Negotiable (can be adjusted as you learn more), Estimable (enough clarity to estimate scope), Small (completable in hours to a couple days), Testable (can be verified as working). If a work item doesn't meet these criteria, break it down further. Don't be afraid to deploy parts of a feature. Regular integration tests help ensure your partial changes remain compatible with the rest of the system.

Small Batches in the Age of AI

With more and more code being AI-generated, small batches become even more critical.

DORA's 2025 research found that working in small batches amplifies AI's positive impact on product performance. Teams that work in small batches see AI accelerate their delivery. Teams that work in large batches see AI create instability. Large blocks of generated code are hard to review, test, and integrate safely.

Small batches act as a safety net. When AI generates code that breaks something, you want to know which small change caused it. If you're shipping large batches of AI-generated code, you've lost the ability to triage effectively.

This exacerbates the need for small, iterative changes where each change is its own feature and all changes are released on their own. Software development is about iterating. Always becoming, never arriving.

Redefining Done

The traditional definition of done in Scrum is "potentially shippable increment." The work is complete when it could be released. That's not good enough.

A better definition of done: running in production, with metrics showing users using the feature, and no major bugs or outages.

This isn't just semantics. It fundamentally changes how teams think about their work.

When done means "code complete," the team's job ends when they hand off to deployment. When done means "users using it," the team's job extends through the entire lifecycle. They care about deployment because deployment is on the path to done. They care about monitoring because they need to see whether users are actually getting value. They care about testing in production-like environments. The dev team has the most impact on the rest of the teams, making everyone’s job easier.

This connects to the Deploy versus Release distinction I made in Part 1. Deploy is a technical decision, putting artifacts in production. Release is a business decision, making value available to customers. The "potentially shippable" definition of done aligns with Deploy. My definition aligns with Release. The difference matters because it determines what the team optimizes for. This is what makes a developer an engineer: someone who takes complete ownership of their code, walks it through to production, watches its impact, and brings metrics back to the team for later iterations.

DORA's research on user-centric focus found that teams who focus on the user have 40% higher organizational performance. This definition of done forces that focus. You can't mark something done until you have evidence users are getting value. It's the capability DORA calls Customer Feedback in action.

In Team Topologies, stream-aligned teams are organized around a flow of work to a user segment. The stream doesn't end at deployment. It ends at user value. This definition of done reinforces that mental model.

This is aspirational for most teams. You need specific technical capabilities to get there: feature flags to control rollout, observability to measure usage, deployment automation to ship quickly and safely. Don't let perfection be the enemy of progress. The goal is to iterate toward this definition, building the capabilities that make it possible as you go.

What Leaders Enable

DORA's research on Transformational Leadership found something important: effective leaders don't drive software delivery performance directly. They enable it by helping teams adopt technical and product management practices.

The five characteristics of transformational leaders are:

Vision: clear direction for where the team and organization are going

Inspirational Communication: making people proud to be part of the team

Intellectual Stimulation: challenging people to think about problems in new ways

Supportive Leadership: considering others' feelings and needs

Personal Recognition: acknowledging good work and improvements

Notice what's not on that list: dictating technical decisions, micromanaging priorities, or controlling how work gets done. Leaders create the conditions for high performance. They don't create the performance directly.

In the planning phase, this means enabling teams to make decisions about tools, technologies, and approaches. DORA calls this Empowering Teams to Choose Tools, and their research shows it contributes to better continuous delivery and higher job satisfaction. Teams that can choose their own tools make choices based on how they work and the tasks they need to perform. No one knows better than practitioners what they need to be effective.

This doesn't mean chaos. Teams still operate within constraints like budget, security requirements, and existing infrastructure. But within those constraints, they have autonomy to experiment and find what works best.

Leaders also enable through Documentation Quality. DORA's research found that documentation quality amplifies the impact of every technical capability they studied. Good documentation isn't just helpful. It's a force multiplier. In planning, this means ensuring teams have access to clear documentation about requirements, architecture, and decisions. It also means creating space for teams to document their own work. Pay attention to decision documentation. Lots of teams have code comments and architecture diagrams. What a lot of teams lack is why certain decisions were made. Software being iterative, you will inevitably revisit a decision. You need documentation that captures not just what decision was made but why. What was the context? What were the priorities at the time? This will help you determine if something in the decision tree has changed or help you remember that one customer who demanded something work a particular way.

Finally, leaders foster a Learning Culture by viewing learning as an investment, not an expense. DORA found that a climate for learning predicts both software delivery performance and organizational performance. Teams that feel safe to fail and learn will experiment. Teams that fear punishment will stick to what's safe, even when what's safe isn't working.

Planning Capabilities Drive Delivery Performance

The capabilities we've covered (generative culture, visibility of work, WIP limits, working in small batches, team experimentation, transformational leadership, documentation quality, learning culture) all predict software delivery performance. And software delivery performance predicts business outcomes: profitability, market share, customer satisfaction.

That's the DORA model. Capabilities predict performance. Performance predicts outcomes.

If you want to improve deployment frequency and reduce change lead time (the throughput metrics DORA tracks), start in planning. Reduce batch sizes. Give everyone visibility into the work. Limit work in progress. Create a culture where information flows and failure leads to inquiry.

Next, we'll look at the Build phase, where planning decisions turn into code, tests, and infrastructure. The capabilities that matter there are different, but they build on the foundation we've laid here. A team that plans well is set up to build well. A team that plans poorly will struggle no matter how talented the engineers are.

Planning is where you win or lose. Take it seriously.

Sources

DORA Research Program and Capabilities: https://dora.dev/capabilities/

DORA Core Model: https://dora.dev/research/

Ron Westrum, "A typology of organisation culture," BMJ Quality & Safety 13, no. 2 (2004)

Team Topologies by Matthew Skelton and Manuel Pais: https://teamtopologies.com/

2023 State of DevOps Report: https://cloud.google.com/devops/state-of-devops

2025 DORA AI Capabilities Report: https://dora.dev/research/